The COVID-19 ‘Coronomic’ Impact: Short-and Long-Term Risks

Having lived in 5 countries around the globe with 3 being in Africa, I’ve had my fair share of diseases such as malaria, typhoid and pneumonia as a kid. When I moved to the Western world, I got introduced to the flu. I know how deadly these diseases can be, but I’ve seen many people handle them with ‘ease’. Therefore, I blamed the public panic over the coronavirus on the hysteria generated by the media. My reasoning was that there are far more diseases like the flu, malaria, etc. that kill more people every year, so I didn’t understand why everyone was panicking. However, looking at the casualty rate vs the flu, the transmission rate and the fact that not much is known about the virus or how it spreads, I realised perhaps the public reaction is founded and I found myself concerned about the wellbeing of people I know around the globe. Being passionate about the markets, I was also curious to know how this will economically affect firms and households across the world on the long and short-term.

The short-term economic risks

After a few days of tracking major market indexes and speaking with a few business executives, I’ve come to realise the recent fall in asset prices may either be the start of a bear market or just a deflationary panic sparked by the media due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Supply chains around the global have been negatively affected by this crisis due to travel restrictions, company shut downs and a decreased aggregate demand as a result of the pandemic. In essence, this crisis has led to a supply and demand problem which makes its economic impact potentially more dangerous than the 2008 financial crisis (which was a demand problem).

The Central Bank’s policy of print money (Q.E) and cut rates to stimulate the economy, seemed to be very popular after the 2008 financial crisis. This measure saved financial institutions during the last financial crisis and brought the global economy back to ‘normal’. With interest rates near zero in most countries since the financial crisis (and even negative in some countries in Europe), companies and individuals have been encouraged to borrow cheap money. This enabled some households to buy assets at inflated prices and some firms to buy back their stocks or allocate money into money-losing acquisitions, hoping this will inflate their stock prices.

However, this pandemic has exposed the flaws of cheap money which has flooded our financial system.

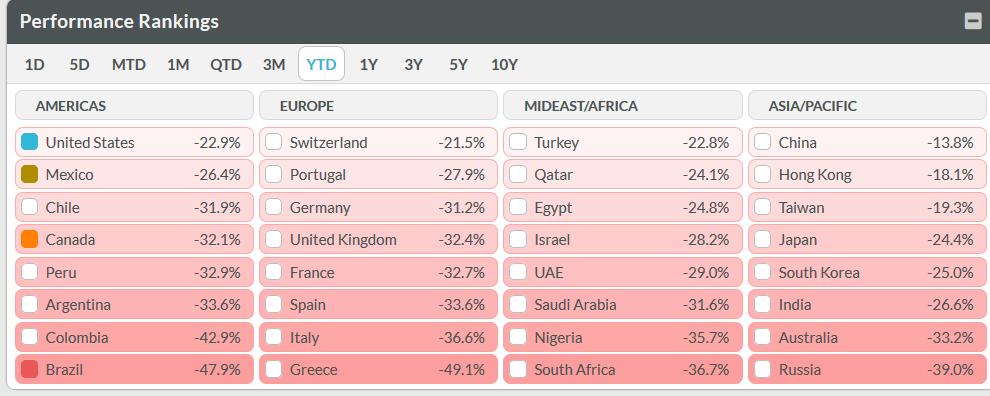

The US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England reduced interest rates to 1% and 0.25% respectively in order to stimulate demand. Yet, this reduction had little effect on demand or stopping asset prices from taking a beating (the Nasdaq, S&P500, Dow Jones Industrial Average, FTSE100, Nikkei225, DAX, and VIX have all dropped over 19%-28% from their peaks this year). Central Banks have little room to lower rates any further except they go into the territory of negative interest rates which might be worse for the economy.

The demand and supply shortage put companies in debt at the risk of not being finance their debts. They will be forced to cut down on spending (through job cuts, etc). Companies that survive may be forced to increase prices due to a supply shortage and an increased market share. Household income will be affected by the job cuts and may not be able to afford goods at high prices which will lead to a lower aggregate demand in the economy. When demand doesn’t match supply then the risks of a recession increases. This suggests monetary policy won’t be enough to manage the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

There has been a call for governments around the world to institute a fiscal policy to curb the effects of the crisis, however, there is a growing debate over whether such measures will stop households and firms that are over-leveraged from taking responsibility for their actions. Perhaps, a fiscal policy that aims at providing financial support for responsible households and firms this crisis would negatively affect is a good thing. Perhaps such fiscal and monetary responses also could include lowering taxes, lowering interest rates, increasing government spending in projects aimed at preventing spread of the virus among the most vulnerable (older folks in nursing homes, etc), creating incentives for healthcare workers who risk their lives to help treat infected patients and funding more research on the disease.

The long-term economic risks

According to the rules of economics (as modelled in the Phillip’s curve), a tight labour market will ultimately force employers to increase wages and the prices of their goods to offset this change. However, this economic theory has been defied in recent years which has been characterised with low unemployment, low inflation and relatively stagnant wages for the middle and working class while asset prices reached all-time highs. While some economists say this is a temporary phenomenon, we’ve seen most governments in developed countries show a willingness to treat this crisis as a national emergency and to spend their way out of this pandemic which may mean a rapid rise in inflation. Moreover, the prices of in-demand goods has significantly increased (due to stockpiling efforts by households/firms and supply shortage problem). This means we could face a period of stagflation.

Central Banks around the world will be forced to increase interest rates to manage inflation caused by the excessive government spending during this crisis. This will probably be after economic growth picks up, which might take a few weeks to a few years. An increase in interest rates has a negative effect on demand and growth. This means the economic slowdown we see today might last longer than we think.

So financial asset prices may not return to where to were at the start of the year. Perhaps this is the start of the much-anticipated correction in the stock market. Whatever the case is, managing portfolio risks during this period of uncertainty will require a mix of skill, luck and patience.

In another turn of events, Saudi Arabia started an oil price war with Russia to gain market share. This led to a sharp fall in oil prices (which may even go lower with a decreasing global aggregate demand). While this might benefit oil-dependent consumers, companies and countries like China especially during this period of economic slowdown, it might lead to other unintended consequences around the globe such as the closure of leveraged oil companies (which are unable to cope with the lower demand for oil and depressed oil prices) and increase unemployment especially in countries that depend on oil exports for foreign revenue.

Global Co2 emissions have significantly reduced as China—the manufacturing centre of the world — struggles to produce the masks and other in-demand products needed during this crisis. Many companies affected by the Chinese Government’s enforced — although much criticised — shutdown of most activities in the regions most affected by the coronavirus (as a response to curbing the spread of the virus) are probably regretting their decision in relying on one company in China as opposed to diversifying their supply chain. The costs savings they may have received from using a single company may not be close to the loss of revenue they’ll experience for not having other suppliers during this period.

A good deal of respected healthcare professionals have warned countries to prepare for more pandemics in the future (which might help prevent an economic catastrophe). So the rapid volatility of financial assets and the economic slowdown that we’ve seen over the past two weeks may be a common occurrence. Interesting times.

Disclaimer: This article was originally completed on the 14th of March 2020.